It’s 10 am in California, 7pm in Egypt. Rush hour traffic has cars bumper to bumper in Cairo but FaceTime lets me slide into the passenger seat with Goya Gallagher – one of Malaika’s founders - at the wheel. Despite a long day, her demeanor is cheerful, engaging. It seems this city energizes her. She confirms that it has not ceased to inspire.

Malaika is a homeware company celebrating Egyptian craftsmanship and its inception has much to do with Goya’s love affair with Cairo. A brief post-graduation visit, a disappointing first job in investment banking and a gut feeling, pushed her to make the leap at the green age of 22. Goya, who is originally from Ecuador, describes landing in Egypt like “travelling to another planet, yet so familiar”.

Ferry from the shores of bustling Cairo to Dahab

Under its spell, Goya was soon joined by her childhood friend Margarita Andrade. With Margarita’s background in design, the women initially began selling linens, starting an embroidery workshop in a small office out of which Goya ran her lifestyle magazine, POSE.

Though the vernacular was perhaps lacking at the time, Goya tells me that Malaika was a social enterprise from the beginning (circa 2004). The founders wanted to celebrate and produce local products, namely world-renowned Egyptian cotton. And they wanted to do this in conditions that they felt comfortable with. At first, this meant training women to hand-embroider for them (locals as well as refugees), with hopes of empowerment and improving their economic situations at the same time.

The Threads of Hope Project - where courses are offered for free and ensure accessibility for women and mothers in particular (with children being welcome).

Through word of mouth, the school’s reputation grew, and the venture has since become its own project, known as Threads of Hope. Established about 2 years ago, this entity has separated itself from Malaika but its mission remains the same. Courses are offered for free, open to all ages and they try to ensure accessibility for women and mothers in particular (with children being welcome).

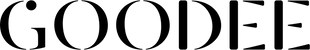

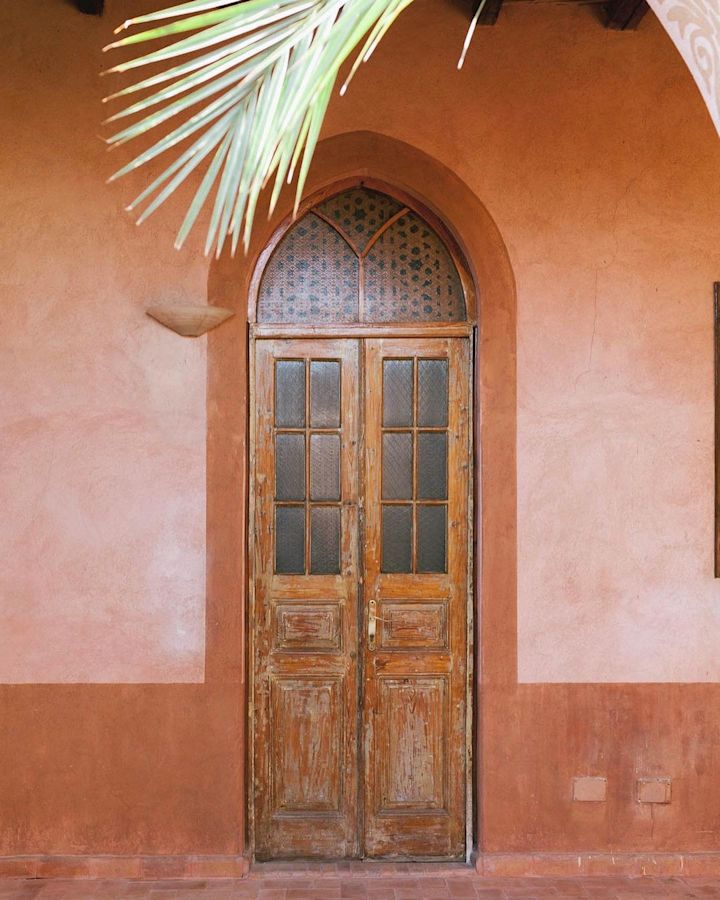

Goya describes Cairo as a crossroads of time and culture, where old world meets new at the turn of a corner. It seems Malaika applies this idea in its approach to homeware. Traditional crafts and methods (and when I say traditional, I mean throwing back to early A.D.s) are practiced and preserved. Local patterns and themes inspire. Yet all of these are revitalized, giving them a timeless quality. Malaika has created a space in which some master embroiderers, who have historically been men, are now taking on female apprentices, ensuring these techniques are not lost. And while they honor that heritage, they aren’t afraid to be playful. Goya describes their winter collection as “a dream-like bohemian-take on ancient Egypt”.

The company has grown organically, at a speed that adapted to the life of their employees as well as their own (especially in regard to having families). Malaika’s “mindful” production extends beyond the social as well. For example, they have transitioned into a made-to-order model. Making samples, rather than inventory, has proven less wasteful and when considering the skill and time invested in each piece, perhaps more sustainable.

The hand-made quality of the brand’s goods is most certainly a luxury in the modern world. Naturally, Malaika’s offering has gradually expanded from linens. A collection of pottery, fabricated by artisans in Fayoum, has been added to the line as well. My interlocutor mentions a potter named Randa with whom she was on the phone earlier. She laughs, delighted to tell me about Randa having to secretly attend pottery classes on Saturdays, defying her father’s wishes. Thankfully, with her persistence and talent, he has since come around to the idea. That “fighting spirit”, Goya sees it daily in the community she surrounds herself with.

The artisan’s stories seem undeniably intertwined with Malaika’s identity. Between two high-pitched honks, Goya admits that the “true pleasure” of this business is the way she engages with the artisans they work with: “Their victories become yours to some degree. It’s truly rewarding”.